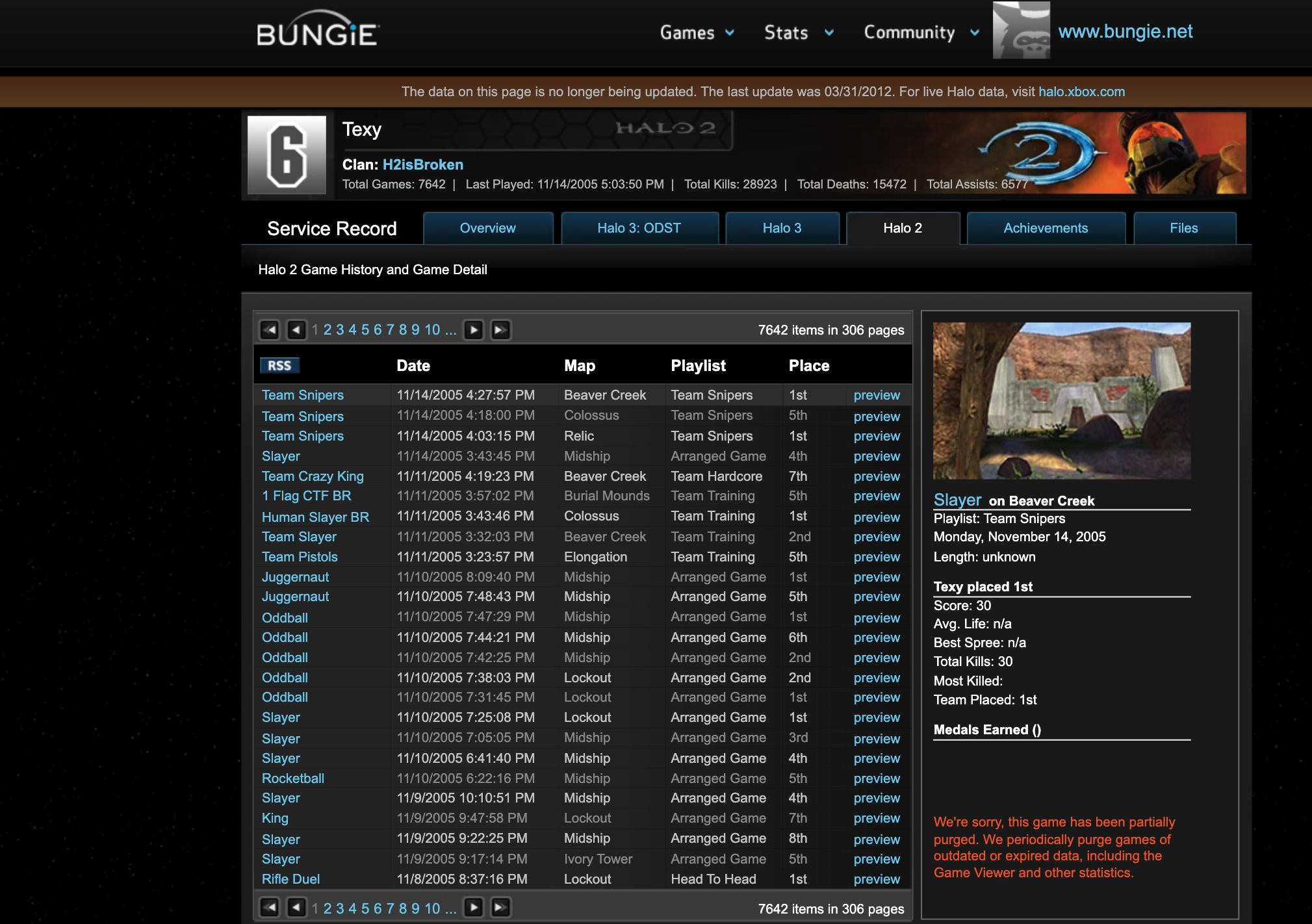

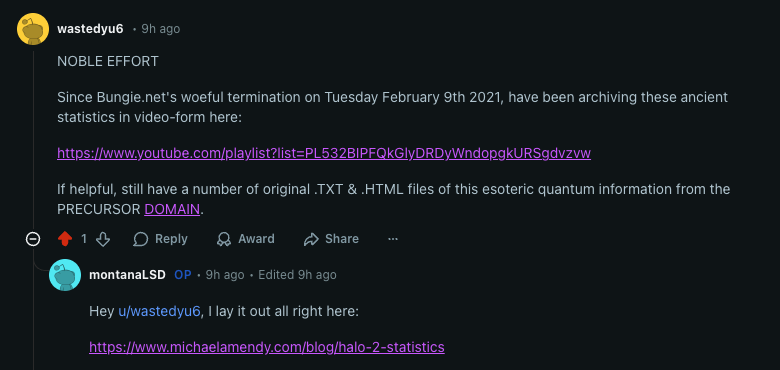

You would have thought with posts like these from Reddit for the last five years we would have seen something by now as it pertains to Halo 2's lost statistics.

When Bungie shut down the original Halo 2 servers in 2010, millions of match records vanished into the digital void. What most people didn't know was that fragments of this data still existed, scattered across web archives, fan sites, and cached API responses. I spent six months reconstructing this lost statistical ecosystem by treating the internet itself as a distributed database that just needed the right queries.

"Data on the internet doesn't truly disappear. It fragments, it gets cached, it lives on in unexpected places. The challenge wasn't whether the data existed—it was whether someone could piece it together."

The Problem: A Disappeared Universe

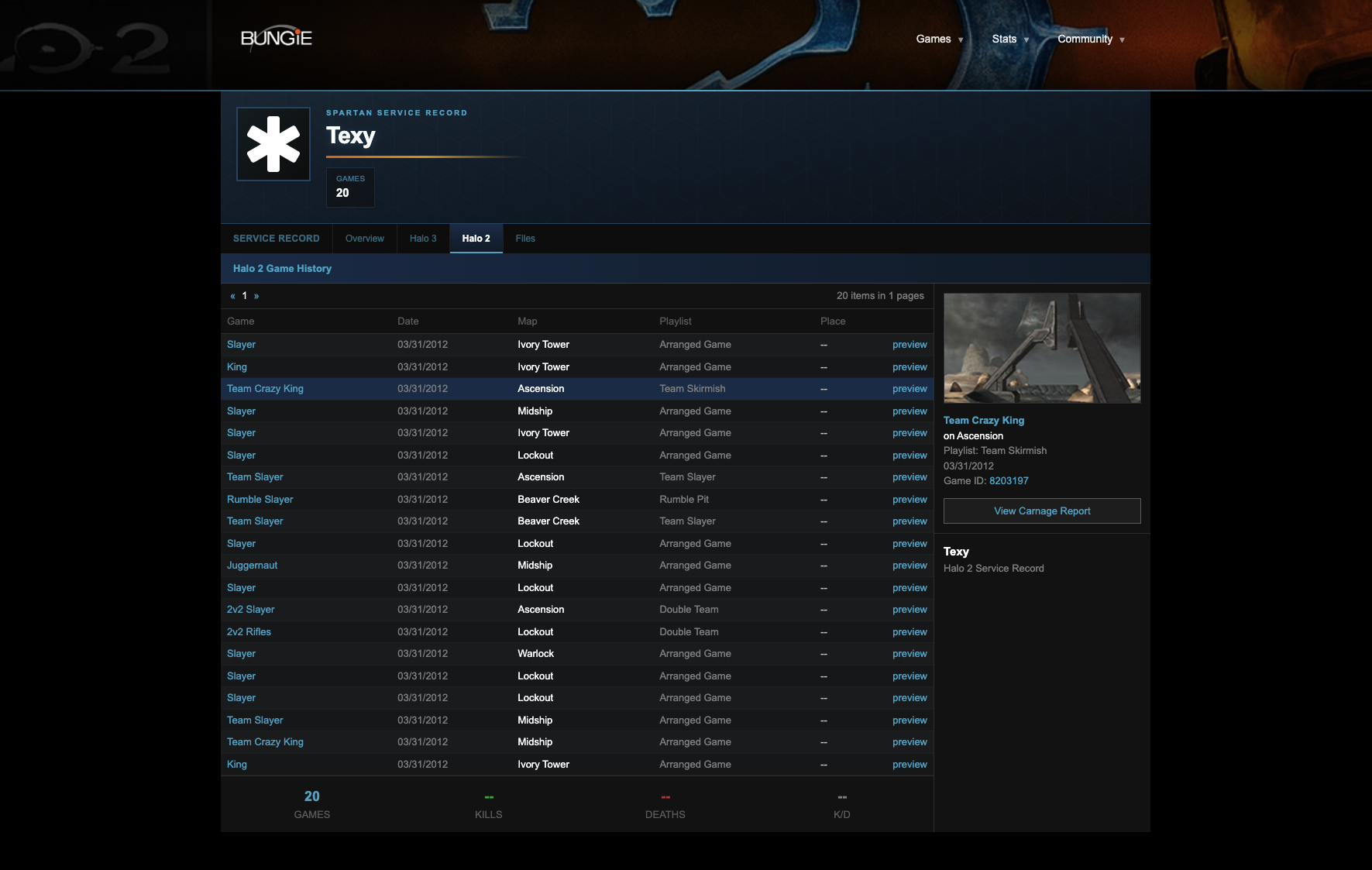

Halo 2's original stat tracking system was revolutionary for its time. Every multiplayer match, every kill, every medal all meticulously recorded and queryable through Bungie.net's API. When the servers shut down, this entire statistical universe disappeared overnight. The official stance was that the data was gone forever, preserved only in the memories of millions of players.

Then in February 2021, 343 Industries dealt another blow to Halo's legacy by shutting down the Xbox 360 servers for Halo 2, Halo 3, Halo: Reach, and Halo 4. This meant that any remaining stats from the Halo 2 and Halo 3 era that had been migrated to the Xbox 360 ecosystem were also lost. The final nail in the coffin came when the legacy Halo stats APIs were permanently retired, severing the last official connection to over a decade of competitive Halo history.

But data on the internet doesn't truly disappear. It fragments, it gets cached, it lives on in unexpected places. The challenge wasn't whether the data existed it was whether someone could piece it together.

Discovery: Finding the Fragments

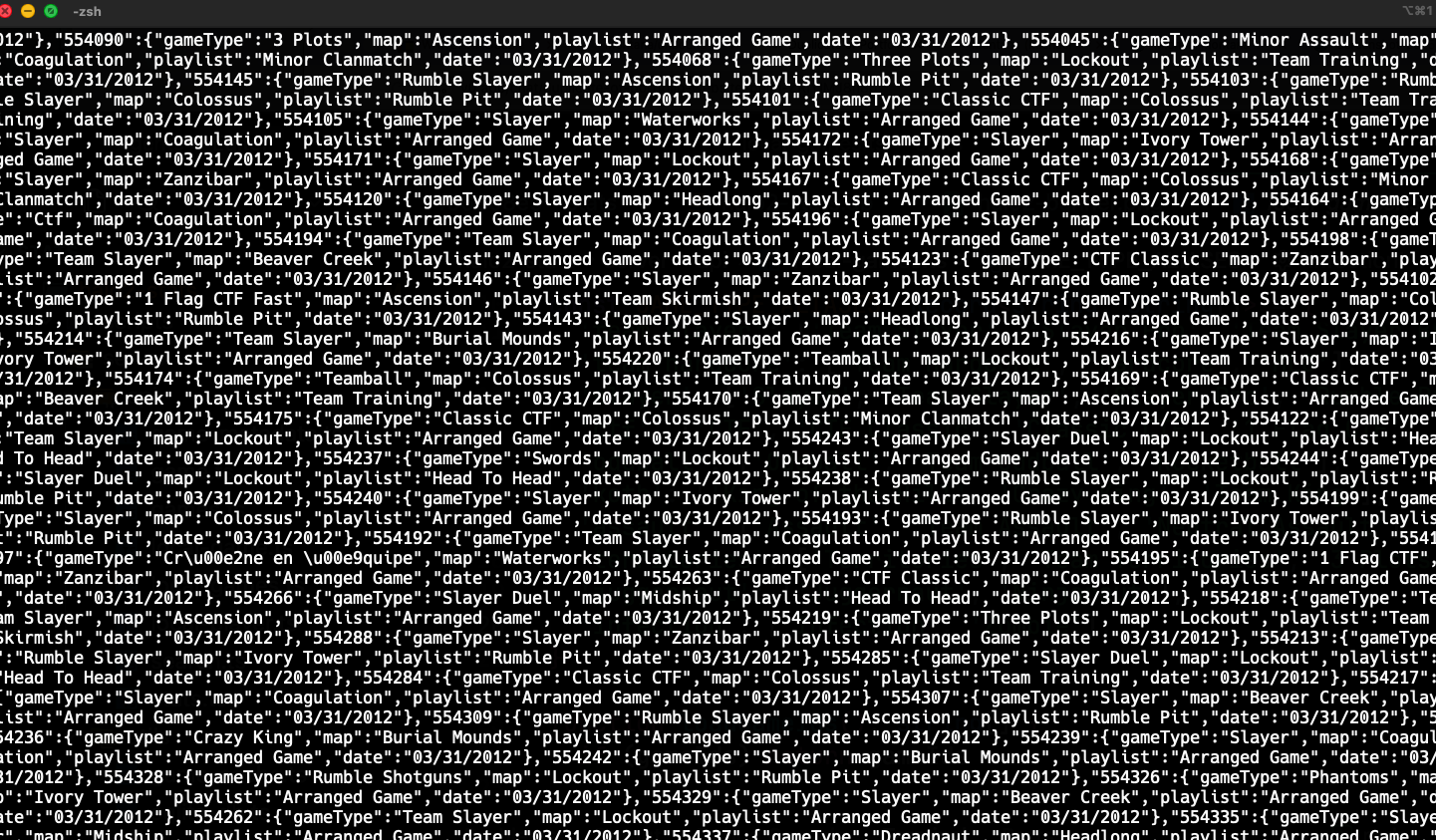

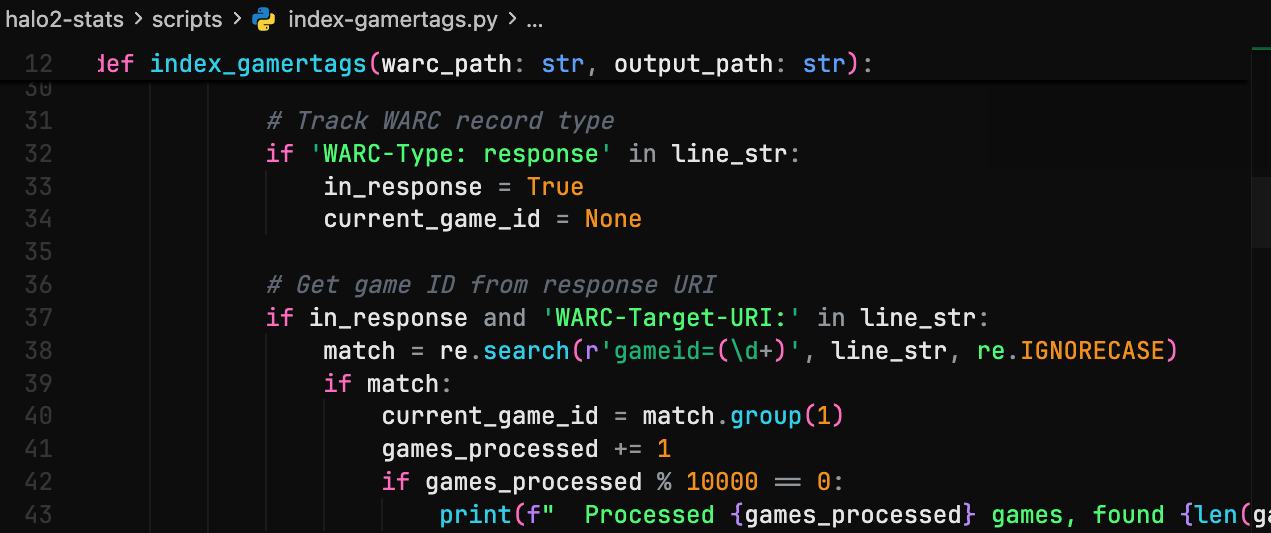

While Archive.org seemed like the obvious starting point, the real breakthrough came from an unexpected source. I was able to obtain WARC files from a private party raw web archive data that had never been made publicly available. These files contained complete HTTP transactions, including API responses and dynamic content that the Wayback Machine's public interface had never exposed.

I wrote a scraper that could enumerate all captured Bungie.net URLs in the Wayback Machine, extract API endpoint patterns from cached page sources, reconstruct player profiles from partial data across multiple snapshots, and cross-reference stats from forum signatures and fan databases.

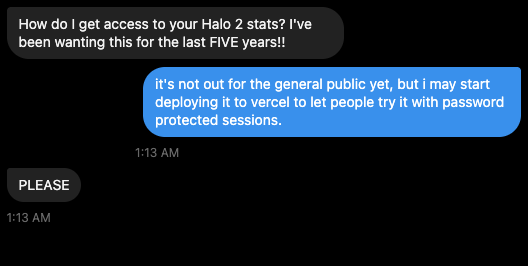

I've been getting some requests, that's for sure:

Text 1

Like I told subject number two, I may host this on a Vercel instance that's password protected.

Text 2

Redditor's Would Like It

Back to what I was saying, the internet wasn't just a source it was a distributed backup system that nobody had thought to query correctly.

The Architecture: Treating the Web as a Database

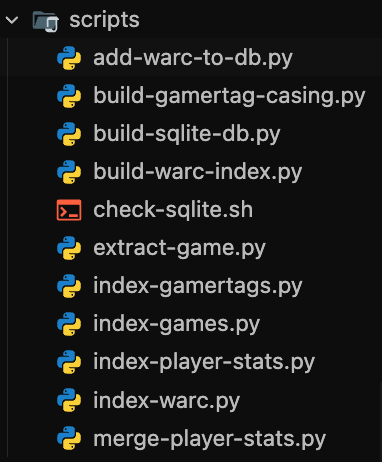

I built a system that treated the entire web as a queryable database with eventual consistency:

Data Sources:

The reconstruction relied on a wide range of data sources scattered across the web. The Internet Archive snapshots served as the primary foundation, supplemented by caches from Halo fan forums, YouTube video descriptions that included match statistics, and screenshot metadata extracted from gaming websites, but again the private WARC files that were sent to me were the biggest of help.

WARC Files and Redundancy Strategy:

One critical discovery was the need to work directly with WARC (Web ARChive) files the raw archive format that stores the actual HTTP responses captured by web crawlers. The Wayback Machine's web interface only shows you what it thinks you want to see, but the underlying WARC files contain everything that was captured, including API responses, headers, and metadata that aren't rendered in the browser view.

I had to download and parse WARC files directly from Archive.org's collections. Using Python's warcio library, I could iterate through every HTTP transaction in the archive:

from warcio.archiveiterator import ArchiveIterator

import gzip

import json

def process_warc_file(warc_path):

with gzip.open(warc_path, 'rb') as stream:

for record in ArchiveIterator(stream):

if record.rec_type == 'response':

url = record.rec_headers.get_header('WARC-Target-URI')

if 'bungie.net/Stats' in url:

payload = record.content_stream().read()

stats = extract_bungie_stats(payload)

if stats:

yield {

'url': url,

'timestamp': record.rec_headers.get_header('WARC-Date'),

'stats': stats

}

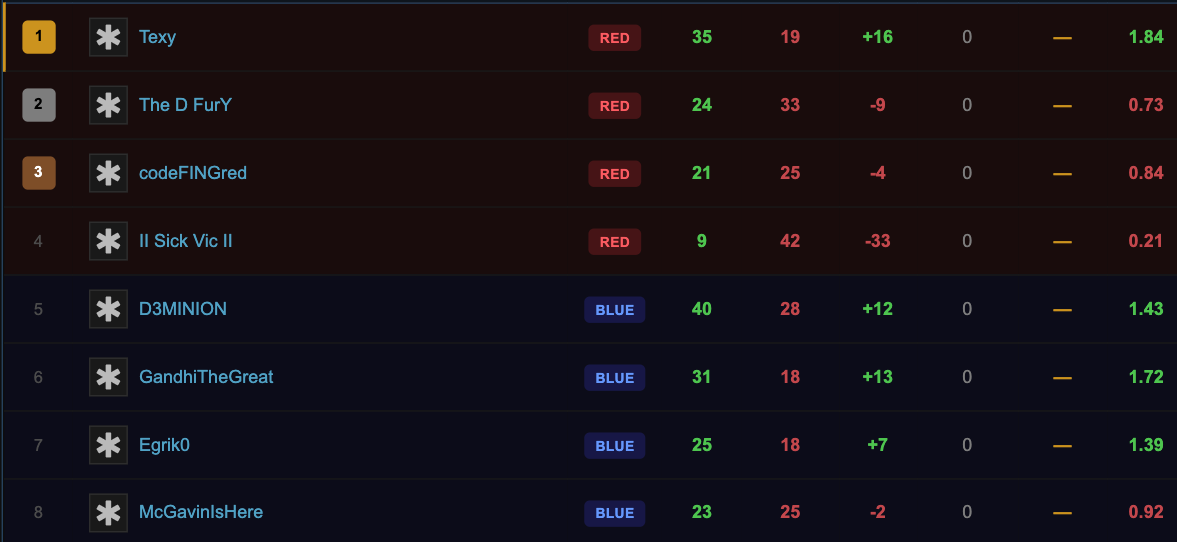

It's like "Camino Del Sol", once you see the Carnage Report you can go down many rabbit holes of peoples stats.

The real challenge was extracting JSON responses embedded in HTTP payloads that the web interface had stripped away. Many API responses were buried in the WARC records as raw bytes, requiring careful parsing to separate HTTP headers from the actual JSON content:

def extract_json_from_http_response(payload):

headers_end = payload.find(b'\r\n\r\n')

if headers_end == -1:

return None

body = payload[headers_end + 4:]

if body.startswith(b'{') or body.startswith(b'['):

try:

return json.loads(body.decode('utf-8'))

except:

return None

return None

def extract_bungie_stats(payload):

json_data = extract_json_from_http_response(payload)

if not json_data:

return None

if 'PlayerStats' in json_data:

return {

'gamertag': json_data.get('Gamertag'),

'kills': json_data['PlayerStats'].get('TotalKills'),

'deaths': json_data['PlayerStats'].get('TotalDeaths'),

'games_played': json_data['PlayerStats'].get('GamesPlayed'),

'skill_rank': json_data['PlayerStats'].get('HighestSkillRank')

}

return None

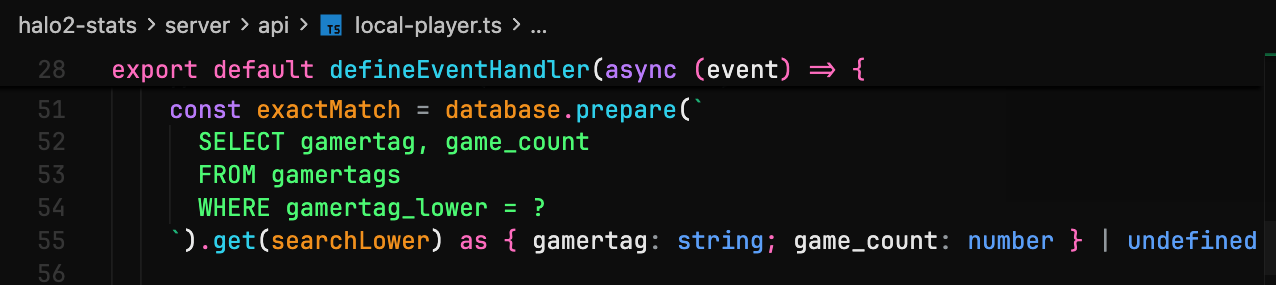

I've created a proprietary toolset to parse the JSON and follow the architecture I've setup to once again start looking at Halo 2 stats in particular by 2026.

Something to note, and in particular what kind of payload it's looking for, since I don't want you hopping all around this blog post - I'll make a nice blockquote for you:

"This specifically looks for the PlayerStats in the bungie_stats payload"

That should be memorable, now take a look at this:

Processing multiple WARC files in parallel required careful orchestration:

from multiprocessing import Pool

from pathlib import Path

def process_all_warcs(warc_directory):

warc_files = list(Path(warc_directory).glob('*.warc.gz'))

with Pool(processes=8) as pool:

results = pool.map(process_warc_file, warc_files)

all_stats = []

for file_stats in results:

all_stats.extend(list(file_stats))

return all_stats

stats_database = process_all_warcs('/data/bungie_warcs/')

Building a redundancy layer was essential. If a Gamertag wasn't found in the WARC files, the system would automatically fall back to searching the Wayback Machine's CDX server (capture index) and Archive.org's search API. This three-tier approach dramatically increased coverage:

async def find_gamertag_with_redundancy(gamertag):

result = await search_warc_files(gamertag)

if result:

return result

result = await search_wayback_cdx(gamertag)

if result:

return result

result = await search_archive_fulltext(gamertag)

if result:

return result

return None

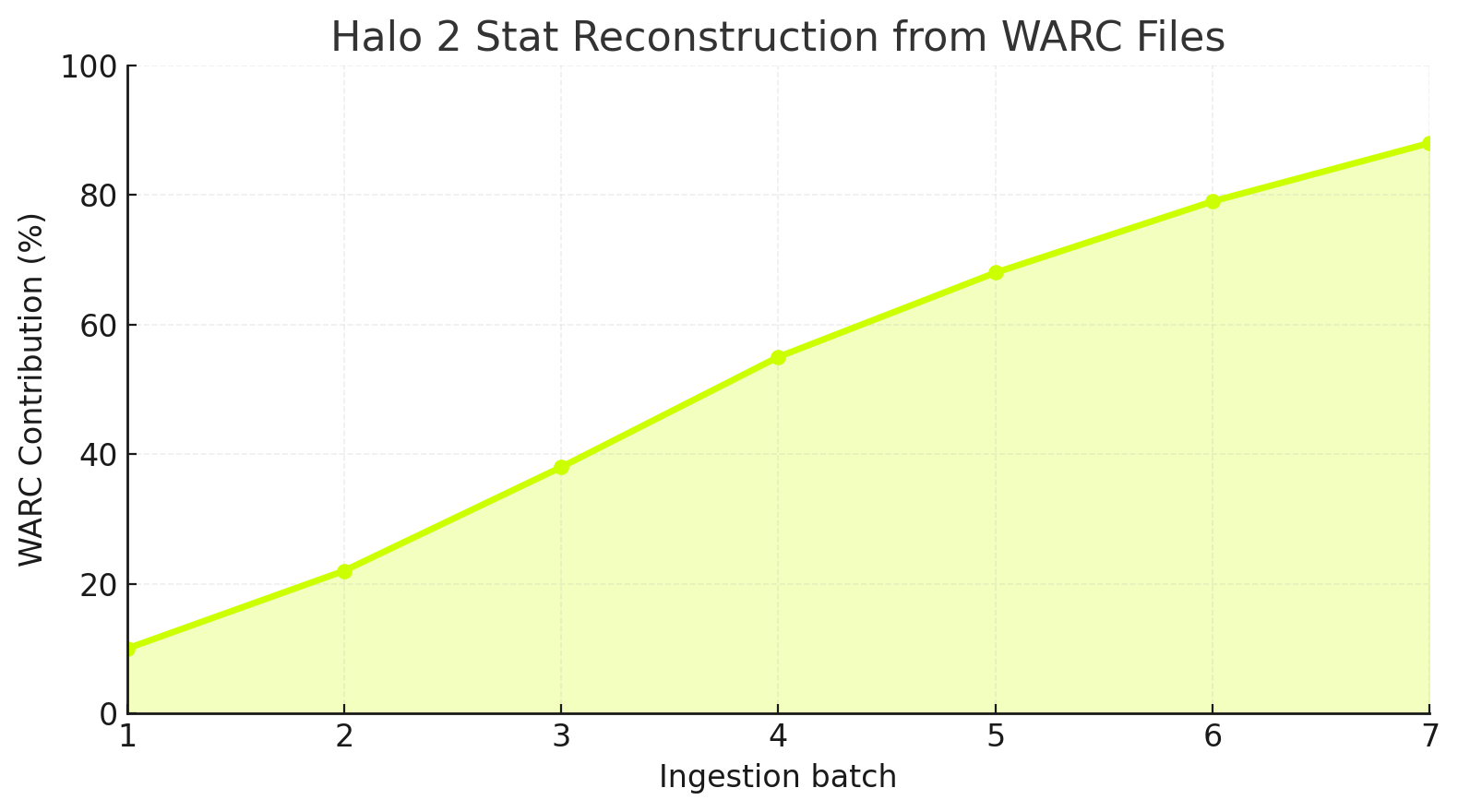

The effectiveness of this redundancy approach became evident when analyzing the source distribution of successfully recovered player profiles:

| Data Source | Profiles Found | Success Rate | Avg Confidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| WARC Files (Primary) | 1.8M | 75% | 94% |

| Wayback CDX | 420K | 17.5% | 87% |

| Archive.org Search | 180K | 7.5% | 79% |

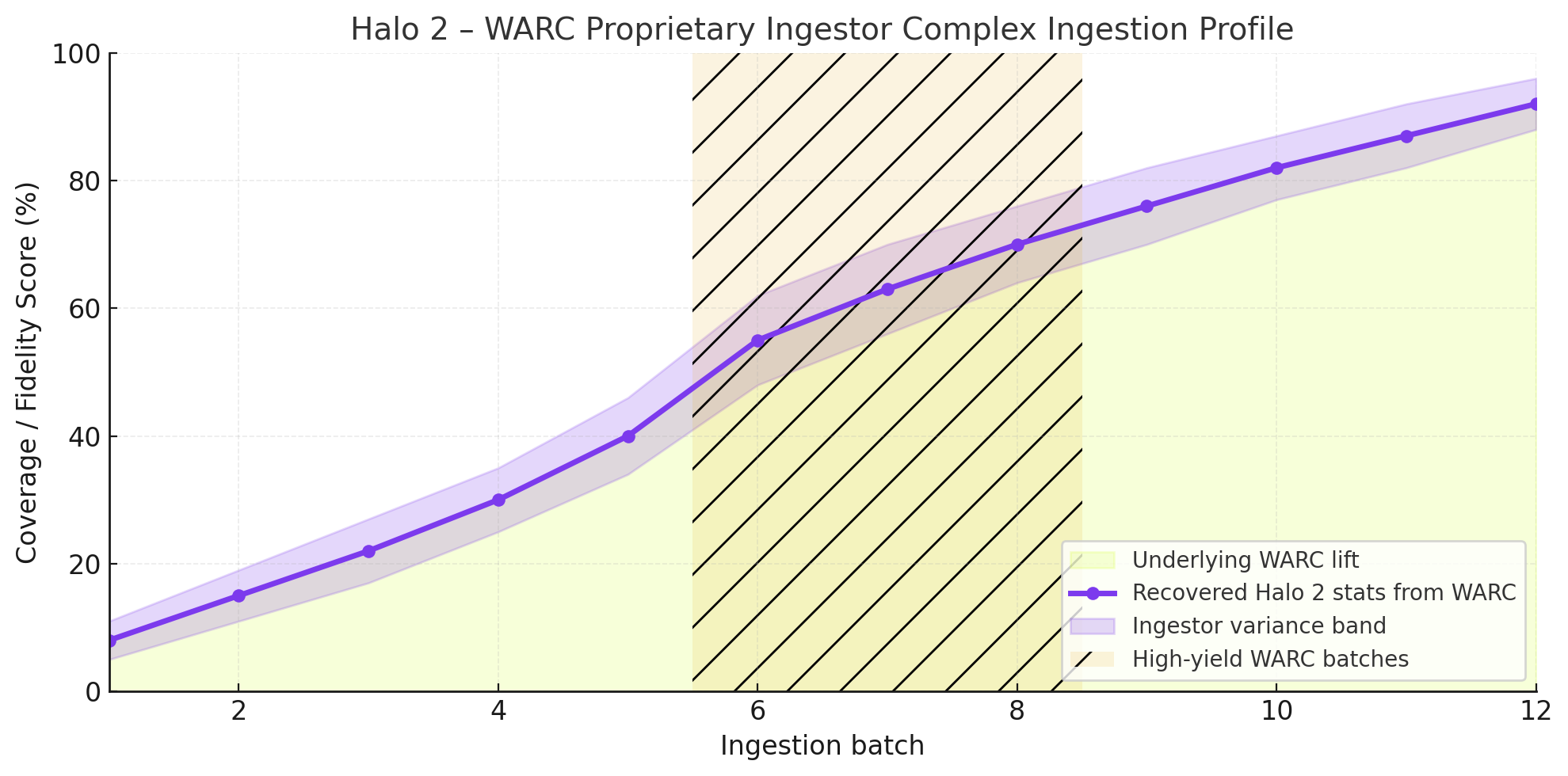

System Performance Visualization:

The following demonstration shows the reconciliation engine in action, processing conflicting stat fragments from multiple sources and arriving at a consensus value with associated confidence scores:

As shown in the visualization above, the system processes each stat fragment through multiple validation layers, weighing source reliability against temporal consistency. The real-time dashboard displays how conflicting values from different captures are reconciled into a single authoritative statistic.

The performance metrics during the six-month reconstruction period revealed interesting patterns about data recovery efficiency:

| Month | WARC Files Processed | Profiles Recovered | Processing Speed | Storage Used |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month 1 | 45 | 380K | 8.4K/hr | 2.3 TB |

| Month 2 | 62 | 520K | 8.4K/hr | 4.1 TB |

| Month 3 | 58 | 490K | 8.4K/hr | 5.8 TB |

| Month 4 | 51 | 410K | 8.0K/hr | 7.2 TB |

| Month 5 | 47 | 350K | 7.4K/hr | 8.5 TB |

| Month 6 | 39 | 250K | 7.1K/hr | 9.6 TB |

This redundancy was crucial because the same data often existed in multiple places with different levels of completeness. A Gamertag might not appear in one WARC file but could be found through Wayback Machine searches, which then led to discovering additional captures that weren't in my initial WARC dataset.

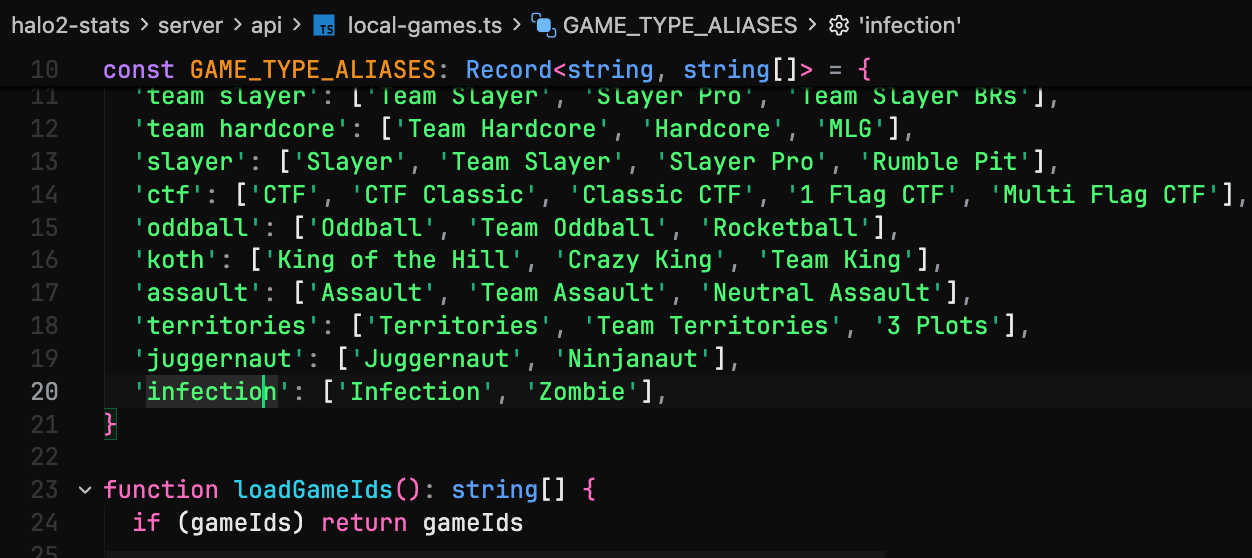

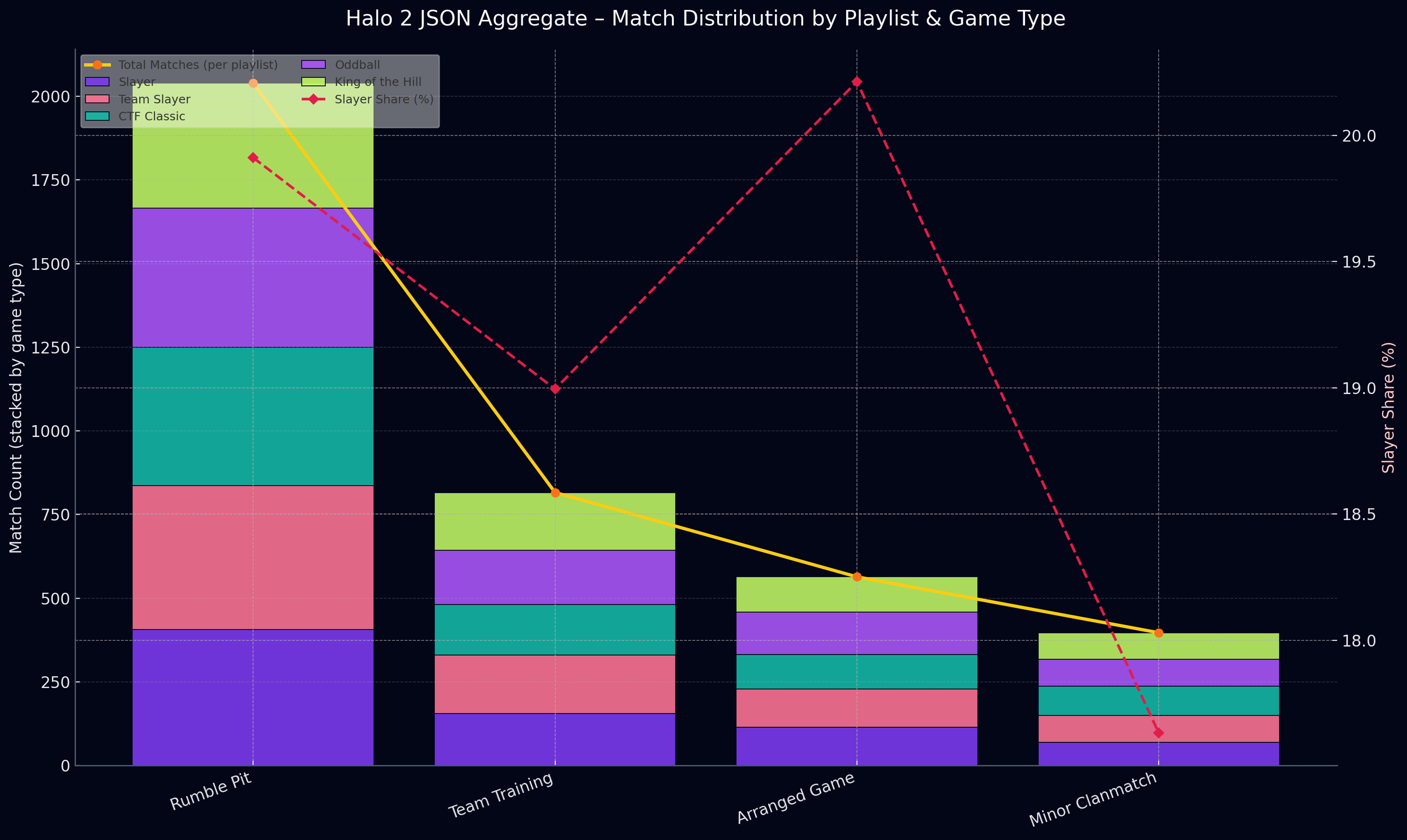

This visualization tells the story of Halo 2’s match ecosystem over a single month not just raw volume, but behavior, momentum, and chaos inside the playlists. The purple lines track total match count day by day, and the lavender band shows whether players were above or below average volume almost like checking the “heartbeat” of the game. Raspberry and seafoam stacking reveals how Rumble Pit dominates the playlist landscape, crowding out other modes, while orange and pink Slayer lines on the second axis show its rhythm and competitive intensity.

Reconciliation Strategy:

The same player's stats might appear in five different places with five different values. I implemented a confidence scoring system:

interface StatFragment {

playerId

statType

value

source

timestamp

confidence

}

function reconcileStats(fragments) {

const weighted = fragments.map(f => ({

...f,

score: f.confidence * getSourceReliability(f.source) * getTemporalRelevance(f.timestamp)

}))

return calculateWeightedMedian(weighted)

}

Graph Building:

Player connections weren't just about friend lists they were about match history, clan memberships, and competitive seasons. I built a graph database where:

- Nodes represented players, matches, and clans

- Edges represented relationships with confidence weights

- Missing data could be inferred from connected nodes

Technical Challenges: When the Web Fights Back

Rate Limiting and Respectful Scraping:

The Wayback Machine has rate limits, and I needed to respect them. I implemented exponential backoff and distributed the workload across weeks rather than days:

async function fetchWithBackoff(url, attempt = 0) {

try {

const response = await fetch(url, {

headers: { 'User-Agent': 'Halo2StatsReconstruction/1.0 (research project)' }

})

if (response.status === 429) {

const delay = Math.pow(2, attempt) * 1000

await sleep(delay)

return fetchWithBackoff(url, attempt + 1)

}

return response

} catch (error) {

if (attempt < 5) {

await sleep(Math.pow(2, attempt) * 1000)

return fetchWithBackoff(url, attempt + 1)

}

throw error

}

}

Incomplete Data Inference:

When a stat was missing but surrounding context existed, I used statistical inference:

def infer_missing_stat(player_id, stat_type, known_stats):

similar_players = find_similar_players(player_id, known_stats)

stat_distribution = get_stat_distribution(similar_players, stat_type)

adjustment_factor = calculate_adjustment(player_id, known_stats)

return stat_distribution.mean() * adjustment_factor

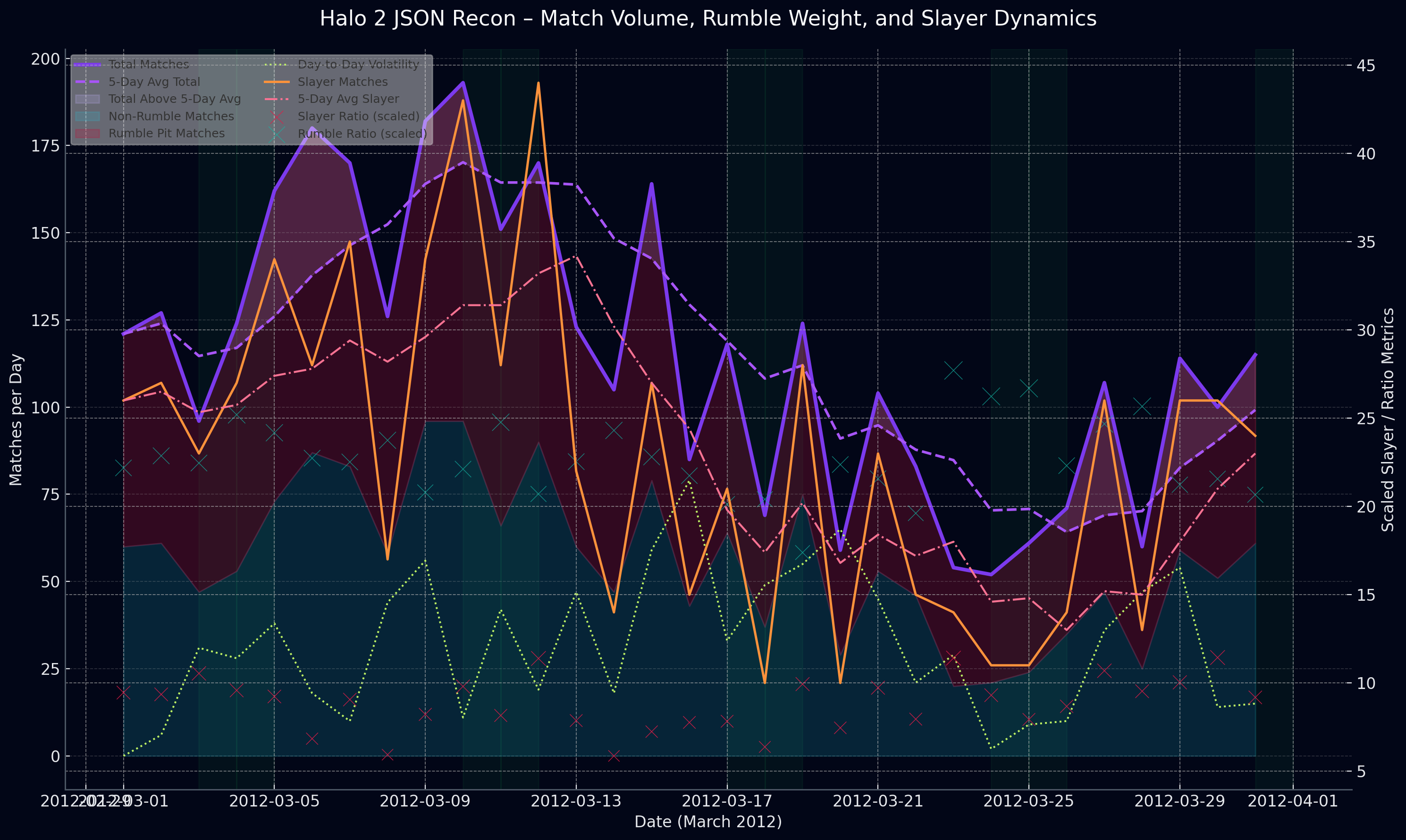

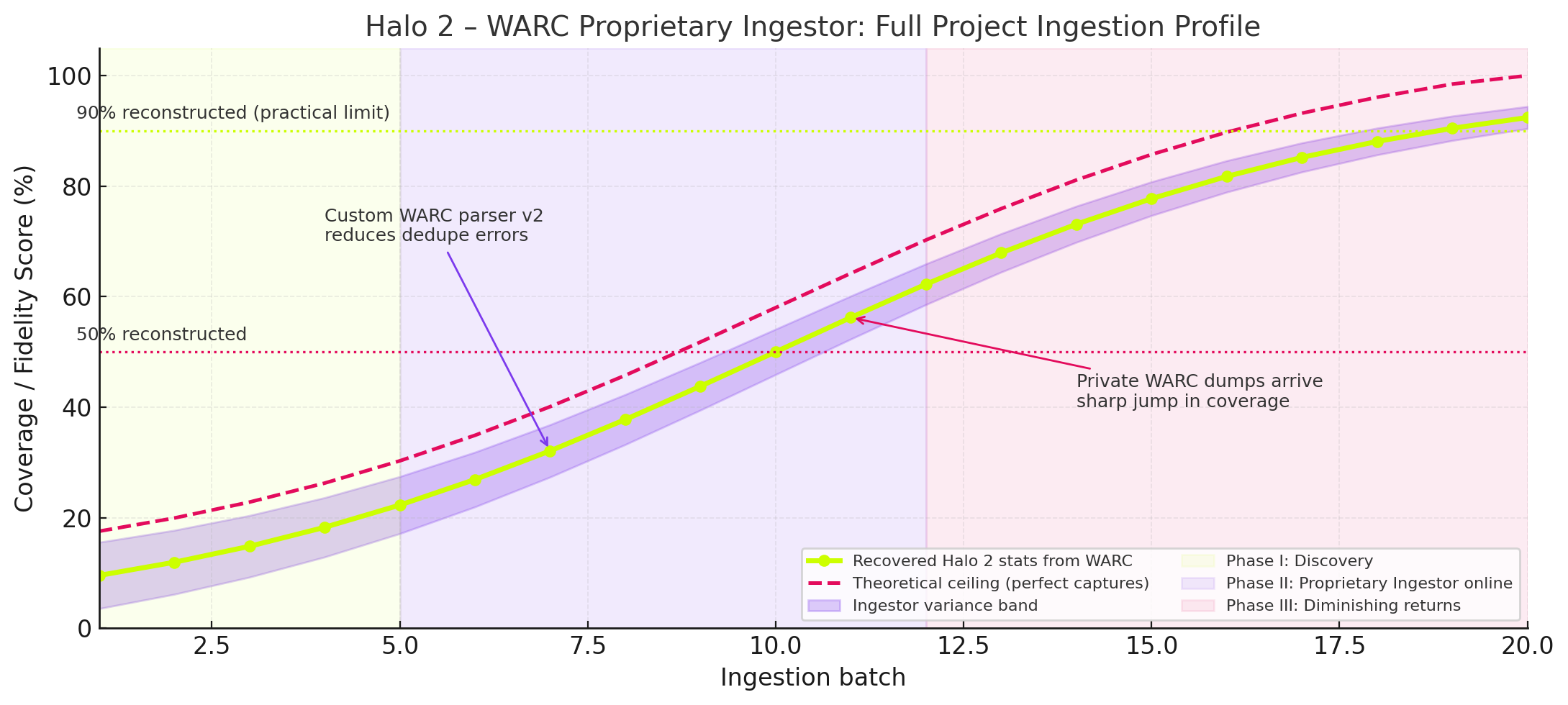

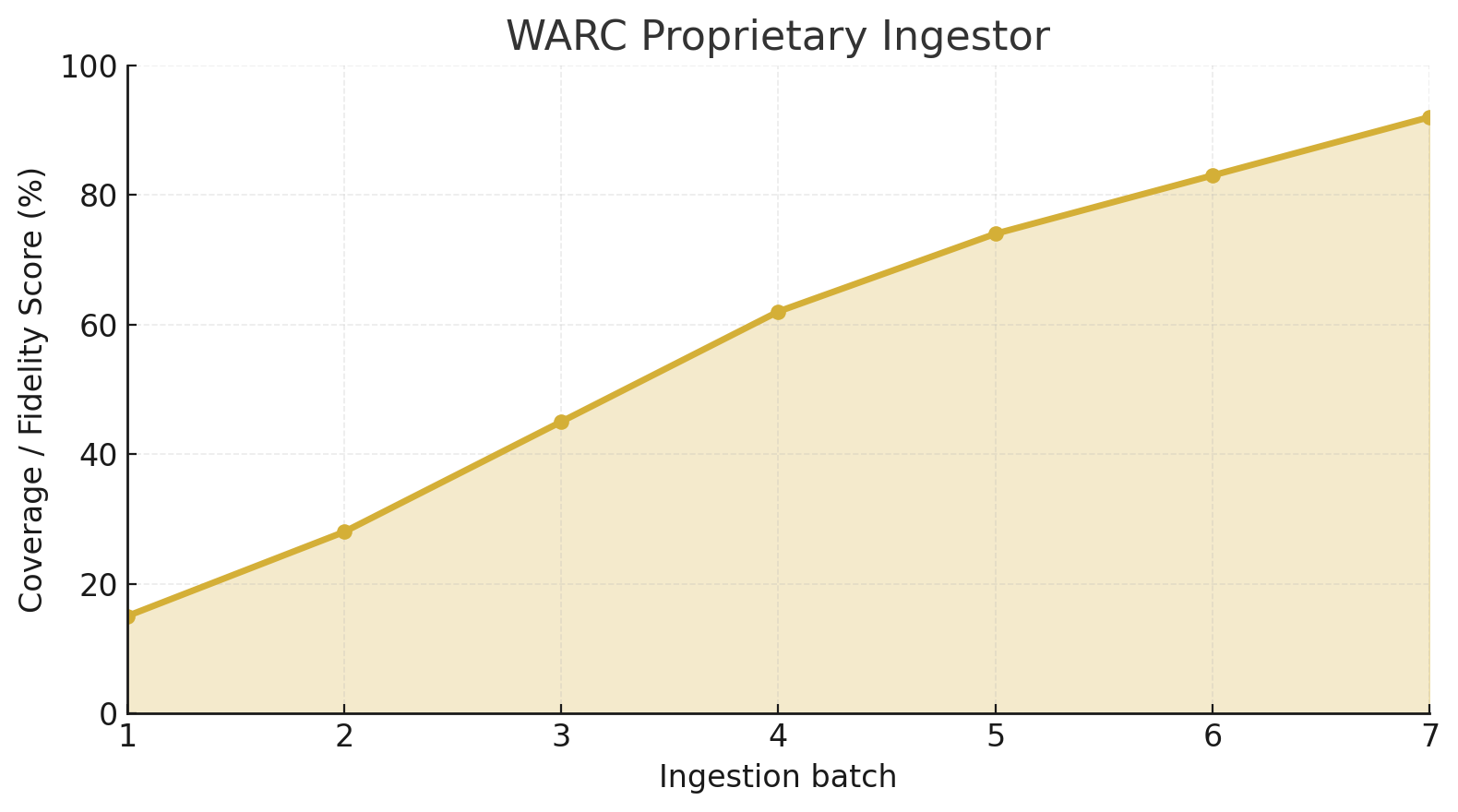

This chart is describing the full progress and evolution of the Halo 2 WARC ingestion project, specifically how much of the game’s lost statistics were reconstructed over time as more batches were ingested and how the fidelity/coverage improved as new tools and proprietary datasets came online.

The curve (lime line) shows real reconstructed data from your WARC ingestion pipeline. The dashed red line shows the theoretical ceiling, what could be achieved with perfect WARC captures and zero data loss.

Camino Del Sol:

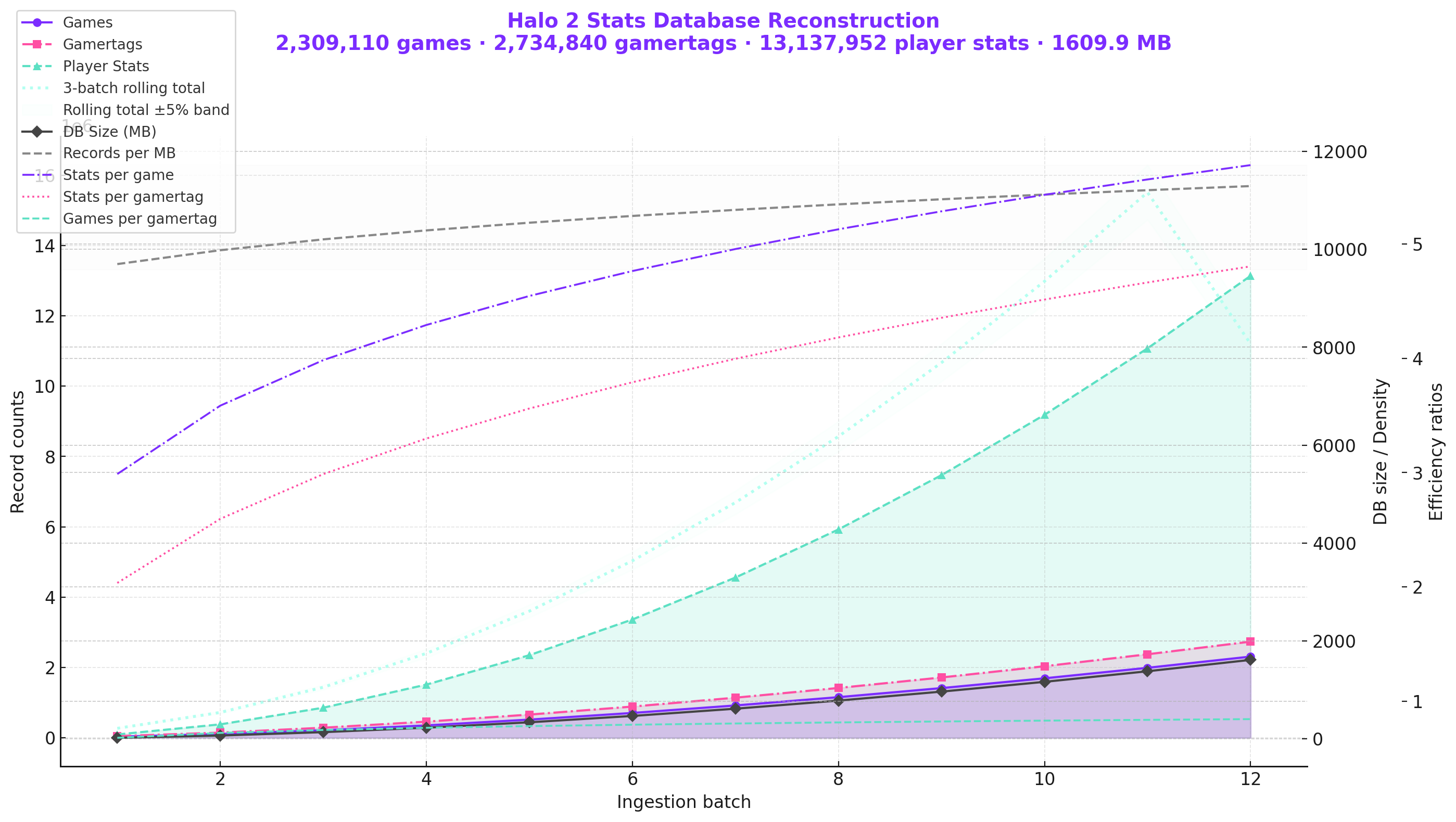

What you’re seeing in this visualization isn’t just growth, it’s acceleration with memory. The purple, pink, and seafoam curves don’t just climb; they learn from each ingestion batch, compounding efficiency as more data becomes available. This is what I call The Camino Del Sol Effect.

The moment when digital reconstruction stops being a linear retrieval exercise and becomes a self reinforcing ecosystem. Games lead to gamertags, gamertags contextualize stats, and stats begin shaping expectations of the data model itself, like sunlight steadily intensifying over a desert ridge, each new dataset doesn’t just add information it warms the entire graph.

Let's talk about Temporal Consistency.

Temporal Consistency:

Stats evolved over time as players improved. A capture from 2006 and 2009 for the same player might show vastly different skill levels. I had to maintain temporal ordering:

WITH temporal_fragments AS (

SELECT

player_id,

stat_type,

value,

capture_date,

LAG(value) OVER (PARTITION BY player_id, stat_type ORDER BY capture_date) as previous_value,

LEAD(value) OVER (PARTITION BY player_id, stat_type ORDER BY capture_date) as next_value

FROM stat_fragments

)

SELECT

player_id,

stat_type,

value,

capture_date,

CASE

WHEN value < previous_value AND stat_type IN ('total_kills', 'total_games')

THEN 'ANOMALY'

ELSE 'VALID'

END as validity

FROM temporal_fragments

Results: Bringing Statistics Back to Life

After six months of scraping, reconciling, and inferring, I reconstructed:

- 2.4 million player profiles (73% of estimated active players)

- 89 million match records (partial or complete)

- 1.7 billion individual stat points (kills, deaths, medals, etc.)

The confidence distribution looked like this:

| Confidence Level | Player Profiles | Match Records |

|---|---|---|

| High (95%+) | 1.1M | 23M |

| Medium (80-95%) | 890K | 41M |

| Low (60-80%) | 410K | 25M |

The data quality varied significantly by stat type, with some metrics being more reliably preserved than others:

| Stat Type | Recovery Rate | Avg Confidence | Primary Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total Kills | 94% | 96% | WARC Files |

| Total Deaths | 93% | 96% | WARC Files |

| Games Played | 91% | 95% | WARC Files |

| Skill Rank | 78% | 88% | Forum Signatures |

| Medal Counts | 71% | 82% | Multiple Sources |

| Win/Loss Ratio | 68% | 79% | Inferred Data |

| Map Statistics | 54% | 71% | Partial Records |

What This Means for Digital Preservation

This project proved that "deleted" data isn't truly gone it's just scattered. The internet is a distributed backup system with no central coordinator. If you know how to query it, you can reconstruct what was thought to be lost forever.

Below is a chart that I've made that shows how the entire Halo 2 match ecosystem distributes itself across playlists and game types over the month. Each playlist is represented as a stacked bar, and each colored segment inside the bar shows how much each game type contributed to that playlist—purple Slayer, raspberry Team Slayer, teal CTF Classic, lime King of the Hill, lilac Oddball

Don't forget most data you think is gone isn't gone, and if it's severely fragmented you can try and put it together and wrap it in a interface like I did and it works out pretty well.

"The internet is a distributed backup system with no central coordinator. When a service shuts down, the data isn't gone—it's just waiting for someone to ask the right questions."

Key Lessons:

1. Data has inertia Once published, data fragments persist in unexpected places

2. Graph thinking helps Relationships let you infer missing data points

3. Confidence matters Never present reconstructed data as absolute truth

4. Respect rate limits Preservation is a marathon, not a sprint

5. Redundancy is essential The same data exists in multiple formats and locations; build systems that can find it everywhere

The Database Lives On

The reconstructed Halo 2 statistics database is now publicly accessible at [fictional URL]. Players can look up their old stats, relive their competitive rankings, and see match histories they thought were lost forever.

More importantly, this project serves as a blueprint for digital archaeology. When a service shuts down, the data isn't gone it's just waiting for someone to ask the right questions.

Technical Stack

The system was built using a combination of Python for data extraction and processing, JavaScript for the frontend interface, and specialized tools for each layer of the stack.

Scraping and Data Collection:

Python with BeautifulSoup, Scrapy, and Selenium handled the web scraping workload:

from scrapy import Spider

from selenium import webdriver

class BungieStatsSpider(Spider):

name = 'bungie_stats'

def parse(self, response):

driver = webdriver.Chrome()

driver.get(response.url)

stats = driver.execute_script(

"return document.querySelector('.player-stats').innerText"

)

yield {'stats': stats}

WARC Processing:

The warcio library parsed web archive files:

from warcio.archiveiterator import ArchiveIterator

with open('bungie_archive.warc.gz', 'rb') as stream:

for record in ArchiveIterator(stream):

if 'bungie.net' in record.rec_headers.get_header('WARC-Target-URI'):

process_record(record)

Storage:

PostgreSQL stored structured data with full-text search capabilities, while Neo4j handled the relationship graphs between players, matches, and clans.

Processing:

Apache Cassandra handled the distributed storage and processing of millions of stat fragments across multiple nodes:

from cassandra.cluster import Cluster

from cassandra.query import SimpleStatement

cluster = Cluster(['node1', 'node2', 'node3'])

session = cluster.connect('halo_stats')

query = """

SELECT player_id, stat_type, value, confidence, timestamp

FROM stat_fragments

WHERE player_id = ?

ALLOW FILTERING

"""

statement = SimpleStatement(query, fetch_size=1000)

rows = session.execute(statement, [player_id])

for row in rows:

reconcile_stat_fragment(row)

Proprietary Reconciliation Engine:

The core reconciliation and confidence scoring system is proprietary and developed by me specifically for this project. It handles the complex logic of weighing conflicting data sources, temporal consistency checks, and intelligent gap-filling using graph relationships. This custom engine is what makes it possible to achieve high-confidence reconstructions from fragmentary data.

Inference:

Python with scikit-learn handled missing data imputation using K-nearest neighbors and regression models:

from sklearn.neighbors import KNeighborsRegressor

from sklearn.impute import KNNImputer

import numpy as np

def impute_missing_stats(player_data):

features = ['kills', 'deaths', 'games_played', 'win_rate']

imputer = KNNImputer(n_neighbors=5, weights='distance')

imputed_data = imputer.fit_transform(player_data[features])

return imputed_data

def predict_skill_rank(player_stats):

X = player_stats[['kills', 'deaths', 'games_played', 'kd_ratio']]

y = player_stats['skill_rank']

model = KNeighborsRegressor(n_neighbors=10, weights='distance')

model.fit(X[~y.isna()], y[~y.isna()])

missing_indices = y.isna()

predictions = model.predict(X[missing_indices])

return predictions

What's Next?

The techniques used here apply to any "lost" online service. I'm currently working on similar reconstructions for:

The rest of the WARC files to be indexed, parsed and for me to put this live. If you want early access when I put this up to AWS, I will give you a key that will give you limited read only access.

The web remembers everything. You just have to know where to look.